Are regional sustainable winegrowing certification programs

a boon for the industry?

By Randy Caparoso

For the longest time, a certified USDA organic seal on a food or beverage product has been the signpost sought by consumers who prioritize the health of the environment and themselves. In the market for domestic wines, however, various certified sustainable seals have become the predominant markers for conscientious shoppers to follow. This, evidently, is not sitting well with some industry observers.

A recent Wine Industry Advisor article, for instance, brought out the inevitable friction between the various organizations competing for the attention of consumers, grape growers and wineries, and the trade and media.

Written by my friend and colleague Deborah Parker Wong, the article was entitled “Navigating the Sustainability Landscape: Which Certifications Matter?” The answer to that question was strongly suggested in the contents of the post: “Beyond the wine industry’s most transparent certifications, which include the CCOF (California Certified Organic Farmers), USDA organic programs and Demeter Biodynamic certification, there is not a single certification governing sustainable winegrowing in the United States that prohibits the use of synthetic herbicides.”

The article cites synthetic applications in vineyards as a litmus test for validity of environmental responsibility.

As further pointed out in the article, “Nearly half of American adult drinkers of beverage alcohol (48 percent) say they are ‘positively influenced’ to buy brands that have demonstrable environmental or sustainability credentials.” Yet, Parker Wong continues, while many of these Americans prioritize “recycling, solar power, water and carbon footprint reductions,” this comes “at the expense of the health of the soil and, in turn, the people who work and live on the land.”

There’s no getting around the fact that the major sustainable programs embraced across the country do allow the use of synthetic herbicides. To the author, this amounts to “the success of the wine industry’s obfuscation” of environmental priorities “behind a logo touting sustainability…. How has the protection of the ecosystem fallen so far down the list of priorities for consumers defined as those who are the most concerned?”

Good question.

Is this another case of big industry pulling the wool over a population’s eyes? Is there a “bad guy” here? Let’s look at a slightly fuller picture.

Looking at the whole picture

Proponents of sustainable programs would say the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides is just one part of the voluminous integrated pest and weed management systems that typically fall under the banner of “sustainable.” Widely followed systems associated with third party certification organizations, such as LODI RULES for Sustainable Winegrowing, typically consist of more than 100 farming practices that address a full range of concerns involving the health and safety of people, products and environment.

Dr. Clifford Ohmart, who, during the 1990s, pioneered the workbooks used in most of the sustainable systems adopted by the winegrowing industry today, points out that certifications such as LODI RULES utilize a PEAS model (that is, Pesticide Environmental Assessment System) for tracking, measuring and managing factors such as pesticide risks. Says Ohmart, “If one looks at the total number of risk points [calculated by the PEAS model] that’s allowed for a growing season under LODI RULES, more than half come from the use of sulfur dust, which is also an organically accepted material, depending on its source.”

A little more than half of the California vineyard acreage certified by LODI RULES now falls within the Lodi appellation. Taking advantage of data on pesticide use that California growers are compelled to file with County Agriculture Commissioner Offices, in 2020 Ohmart compiled a report entitled Lodi Growers Reduce Pesticide Risk. Although only one-quarter of Lodi vineyards are certified sustainable, the numbers show that, since 1999, use of pesticides within the region as a whole has declined by 81 percent and reduction of high-risk pesticides by 89 percent. During the same time period, use of herbicides with potential to leach into groundwater has declined 62 percent. Use of sulfur, widely used in conventional, sustainable as well as organic farming, has declined by 23 percent.

Pesticides in organic farming

One of the goals of sustainable movements, reiterates Ohmart, “is striving to reduce pesticide risk. The reality is that pesticides, both organically approved and conventional, will always play an important role in agriculture. That is because we will always have pests, no matter how natural we try to make our farming.

“The take-home message is that all pesticides used in farming — whether organic, Biodynamic or synthetic — have a level of risk associated with their use. Yet so many people who see the terms organic or Biodynamic think ‘no pesticides.’ This is a huge misconception.”

A widely circulated article in Scientific American entitled Mythbusting 101: Organic Farming > Conventional (Wilcox; July 18, 2011), minced no words about this fact about the agricultural industry: “Many large organic farms use pesticides and fungicides liberally.” While certified organic farms may, in fact, routinely spray with pesticides, there are farms that are pesticide-free which, nonetheless, cannot attain organic certification because they might use a synthetic herbicide, even if only once per year. In a more recent AgDaily post, Top 7 myths about organic farming (Miller; March 15, 2022), it is pointed out that the USDA has approved more than 8,000 branded pest-control products, many of them “very similar to conventional, just with an inert ingredient or two changed.”

There’s plenty of research pointing out that, while organic farms are generally assumed to use fewer herbicides and pesticides than, say, conventional farms, the metrics don’t actually bear this out. In a recent comprehensive study entitled Identifying and characterizing pesticide use on 9,000 fields of organic agriculture (Larsen, Powers, McComb; September 2021), you find tables demonstrating that certified organic vineyards assessed in Kern County have been spraying with more pesticides than conventionally farmed vineyards.

Full disclosure: I live in Lodi, where there’s a strong preference for sustainable winegrowing. Then again, there’s now a stronger preference for sustainability throughout California and in other states with significant wine industries. In Lodi, there are also numerous growers and winery owners who farm both sustainably as well as organically, rather than just one or the other. There are even some vineyards in Lodi that are certified by Demeter for Biodynamic farming, on top of qualifying for sustainable certification.

The Lodi appellation is more a farming rather than a “winery” region, consisting primarily of independent landowners or groups that have invested in vineyards to capitalize on the wine market. A handful of the larger growers also own their own wineries, where they are able to process their grapes for the bulk wine market, as well as do a considerable amount of custom winemaking and bottling. Grape growing in Lodi is a business, much like any other in the agricultural industry, and most of this business is geared towards meeting the needs of wineries and their marketing priorities, which may or may not entail organically or sustainably grown grapes.

Sustainability over organic

I recently asked Bokisch Vineyards’ Markus Bokisch, who sells as well as custom crushes grapes from vineyards that are certified both organically and sustainably, for his perspective on the two approaches. He writes:

I think that our grower community prefers sustainability because it is a more quantifiable approach to farming. Many consumers may prefer “organic” because, frankly, they find that term to be more appealing. My main motivation for farming sustainably is to pass a property down to the next generation in a better condition than I inherited it. Improving wine quality, in that sense, might be secondary to sustainability.

If, however, I were to choose just one of the programs, one that would lead to improved farming practices, I would choose sustainability over organic, because it is more holistic in its approach to farming and better addresses our ultimate goal of property stewardship. It is also more difficult to achieve.

LODI RULES, for instance, directly tackles six aspects of sustainability — business management, human resource management, ecosystem management, soil management, water management and pest management. The program also quantifies the toxicological impact to almost all of the inputs used in farming through its Pesticide Risk Model. If you fail any one of these chapters, you are decertified. This is a high bar to meet, and it requires a lot of documentation and time.

Set a low-yet-broad bar

Unlike Bokisch Vineyards, Lodi’s The Lucas Winery does not supply grapes to other wineries. All of its fruit goes into its estate grown wines. For nearly its entire existence (the winery was founded in 1978), the Lucas family’s vineyards have been certified organic by CCOF. In recent years, to meet expanded goals, they have also been farming sustainably.

In the past, co-owner/winemaker Heather Pyle Lucas has been diplomatic when comparing organic and sustainable programs. But in a recent, more candid, moment, she made these observations:

Set a low-yet-broad bar

Unlike Bokisch Vineyards, Lodi’s The Lucas Winery does not supply grapes to other wineries. All of its fruit goes into its estate grown wines. For nearly its entire existence (the winery was founded in 1978), the Lucas family’s vineyards have been certified organic by CCOF. In recent years, to meet expanded goals, they have also been farming sustainably.

In the past, co-owner/winemaker Heather Pyle Lucas has been diplomatic when comparing organic and sustainable programs. But in a recent, more candid, moment, she made these observations:

The goals of organics and sustainability are equally important to us. Since I work with both CCOF and LODI RULES regarding compliance, I just don’t see how one is more transparent than the other. Since we get asked about the differences all the time, though, I know there are a lot of misconceptions, and misinformation is rampant.

If you think organic compliance is the more environmentally responsible or difficult approach, I would suggest that you ride along with an auditor for LODI RULES one day to see how complex this program really is, and the level of commitment it takes a grower to achieve this certification.

A good sustainable program does focus on multiple facets towards improving the Environment — with a capital E — which include workers, business profitability, emissions and water conservation, among other considerations. It excels in many areas at once with clear, concise metrics that demonstrate the program’s values (for example: It’s okay to do X but even better to do Y or Z). I personally learned a tremendous amount just by applying the point scores in another grower’s operation. It’s important that the evaluation/point system sends a clear message to growers as to what is considered to be the most important goals, and to consider changing if possible.

At the same time, one of the compelling aspects of a good sustainable program is that it also has a low-yet-broad bar, or barrier, for entry. This makes it inclusive, which brings about a broader base of growers focused on what practices are most detrimental and what practices are “sustainable.” It’s a system that invites participation, but encourages constant improvement.

I would say, though, that you can’t judge a system based only on the use of one thing, such as Roundup, even with all the brouhaha surrounding glyphosate. I agree we should get away from it, but sustainable programs, while allowing [the herbicide] also reward allowing weeds. Weed control is a problem, but less so than what we use to achieve it. Beneficial organisms don’t care how weeds are removed, they just don’t find a habitat in land devoid of grasses and other weeds.

If you want to poke holes in sustainable programs, you would have to throw the net over organics, too, especially its reliance on sulfur dust — its biggest flaw being, as a generalist pesticide like many others, it knocks back both good and bad organisms.

On the balance, you have to say sustainable programs are more holistic — and certainly much more comprehensive. Organic farming is more rote and not nearly as transparent as you may think. When inspectors come and we ask about movements towards things like wildlife corridors, or hedgerows for beneficial insects, we draw a big blank. CCOF may have guidelines for that, but they are not particularly well enforced.

And besides, the USDA’s entire National Organic Program structure, which rewards the companies that put in the big money to get on the list of allowed herbicides and pesticides, has a distinct air of clubbiness, not entirely savory. It’s clear enough to me which practices have a more positive environmental impact, and it’s not organics.

Move the needle

Dr. Stephanie Bolton, who serves as Lodi Winegrape Commission‘s director of grower education and sustainable winegrowing, adds these final words to the conversation:

I think it’s good to be critical of certifications. Anyone can find fault in organic or sustainable systems. But picking apart the various programs probably just adds to any distrust or confusion, especially among consumers. No program will ever be perfect, but they can be better.

Getting away from the worldwide over-use of synthetic herbicides, for one thing, is a great goal to have. We happen to be planning an upcoming weed outreach meeting. For this we are creating visual life cycle diagrams, illustrated by an artist, listing the top ten troublesome weeds in vineyards so that the growers can clearly recognize them when they go to seed. I plan to play a game to identify these weeds out in a vineyard. We’ll also show some new and old non-chemical technologies for weed management, and talk about the acceptance of some weeds on a vineyard floor.

It’s easy to wrap your mind around just one or two aspects of any comprehensive farming system that you might find objectionable. The reality is that none of us will ever fully understand all of the implications of what we do to the environment and to people, especially on a global scale. Our lens simply isn’t wide enough. It’s more important, I think, to take actions that move the needle in the right direction.

My take: It’s all good — sustainable, organic, Biodynamic, all the variations of today’s regenerative protocols being applied in today’s vineyards, with or without certifications. So what if there are multiple seals on wine bottles? The consumer is smart enough to know that the industry is contributing to environmental protection in more than one way.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

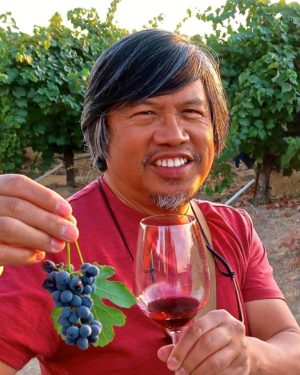

Randy Caparoso

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist/photographer living in Lodi, California. In a prior incarnation, he was a multi-award winning restaurateur, starting as a sommelier in Honolulu (1978 through 1988), and then as Founding Partner/VP/Corporate Wine Director of the James Beard Award winning Roy’s family of restaurants (1988-2001), opening 28 locations from Hawaii to New York. While with Roy’s, he was named Santé’s first Wine & Spirits Professional of the Year (1998) and Restaurant Wine’s Wine Marketer of the Year (1992 and 1998). Between 2001 and 2006, he operated his own Caparoso Wines label as a wine producer. For over 20 years, he also bylined a biweekly wine column for his hometown newspaper, The Honolulu Advertiser (1981-2002). He currently puts bread (and wine) on the table as Editor-at-Large and the Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal (founded in 2007 as Sommelier Journal), and freelance blogger and social media director for Lodi Winegrape Commission (lodiwine.com). You may contact him at randycaparoso@earthlink.net